Notes on the Research and Development of a multi-channel video project as part of Jet-Black Futures.

|

The influence of the work of Nam June Paik, in relation to his engagement with the video ‘glitch’ and the sculptural physicality of the Cathode Ray Tube, both within and without its standard enclosure of the Video Monitor or Television Set, has impacted my practice since the 1980s.

During my time studying for a MA in Environmental Media at the RCA (1984-86), I had conducted a few rough forages into the use of the basic two machine Sony U-Matic editing suite that was available to students on the course. The resultant crude video experiments didn’t feature in my final Degree Exhibition and this aspect of my practice remained temporarily on hold.

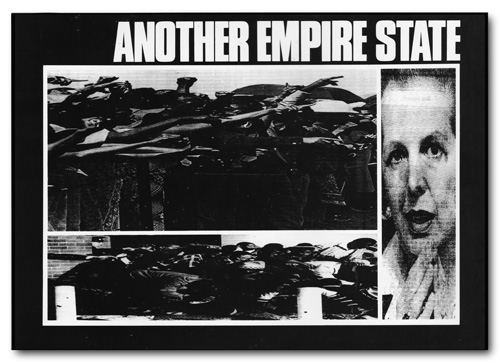

However, my engagement with video was to resurface in a solo exhibition held in Battersea Art Centre, London in September 1987 entitled ‘Another Empire State’. This exhibition took the then ongoing struggle against the racist Apartheid regime in South Africa, and the active support of that regime by the UK Government of Margaret Thatcher, as its central theme.

The work employed recorded televisual broadcast news-footage of political unrest in South Africa, ‘crash-edited’ from a domestic VHS video deck onto a Low-Band U-Matic recorder. The resultant grainy, glitchy footage forming an impressionistic video montage of ‘found footage’.

For the installation, ageing ex-rental television sets donated to the project by the Stockwell Road branch of the Rediffusion video rental company, were positioned onto a large timber framework suggestive of a crucifix.

A single U-Matic player outputing a video signal, modulated to RF, is passed through a ‘splitter', and then fed individually to each ex-rental television set. Each television set therefore received the same video signal, but due to variations in the quality of each set’s ageing components, they each rendered a different pattern of pixelated imagery and interference, ranging from recognisable footage to abstract ‘snow’.

This work could be seen as an attempt to deploy this glitched and ‘trembling’ imagery as a way of commenting on the distorting role of the media and its output devices, even when we hold them in implied religious reverence.

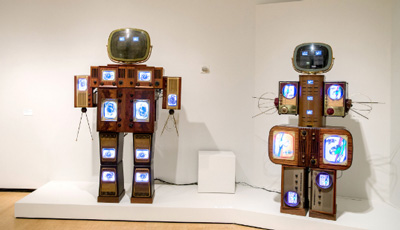

Following this initial engagement with video within my art practice, but also frustrated by the inaccessibility of anything but the most basic video editing/post-production tools, during the late 1980s, I became increasingly interested in the emergence of low-cost home computing machines. Principally aimed at the ‘computer-gamer’ user group, these machines also provided interesting and accessible production tools for independent creative practitioners.

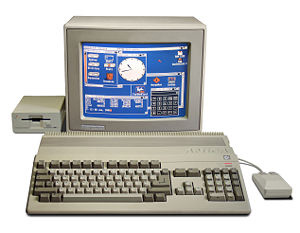

1985 was to see the release of two home computing platforms, both of which were arguably to significantly impact cultural and media practices of the time. These were the Atari ST and the Commodore Amiga.

|

|

|||

As explored elsewhere, the Atari was to revolutionise independent music production through the mid 1980s and beyond, through its unprecedented ‘MIDI’ friendly design. Meanwhile the more expensive Apple Macintosh was starting to establish its dominance of the emerging domain of ‘Desktop Publishing’, against the backdrop of the stranglehold which the ubiquitous ‘PC’ running ‘Microsoft Windows’ was having on the office and business sector.

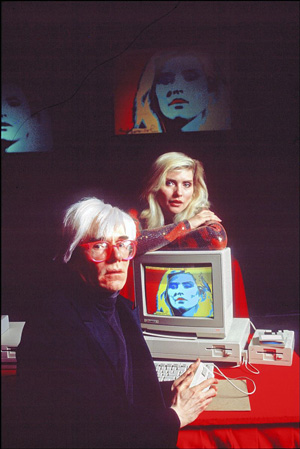

However, the Commodore Amiga, launched in the same year as the Atari ST (as a sort of warring bastard sibling), was to pitch its tent in a different and novel domain. Emerging with, at the time and price point, revolutionary image handling abilities, Commodore was to stage a fascinating (but strangely until recently overlooked) gesture at the launch event for the Amiga in Lincoln Centre, New York on the 23rd July 1985. Art historian Anjalie Dalal-Clayton visits this event and its implications in depth in her soon to be published essay ‘Technological Journeys in the Work of Keith Piper’. Following the customary introductions to the Amiga by company executives, Commodore invited Andy Warhol, one of the most celebrated visual artists of the time to the stage, alongside Deborah Harry, one of the most iconic music stars to demonstrate the image manipulation and paint-box functions of the new computer.

|

|

When Andy Warhol went on stage to manipulate a digitised image of Deborah Harry using ‘Pro-Paint’ on the newly launched Amiga 1000 computer, this represented Commodore’s attempt to position itself as the ‘go-to’ platform for visual creatives, and Warhol’s attempt to align himself with all that was new and ‘sexy’ in contemporary culture.

Andy Warhol demonstrates the Amiga 1000 at Launch Event. 1985 Lincoln Centre New York |

|

Working with his friend and collaborator Deborah Harry, a figure who having emerged from and transcended the ‘Punk’ movement of the 1970s to achieve celebrity iconic status in the 1980s, was at the centre of tantalising on-going speculation around her similarity with one of Warhol’s most iconic early subjects, Marilyn Monroe. Some of this went as far as speculating that Harry, who was adopted as an infant, may have in fact been Monroe’s daughter.

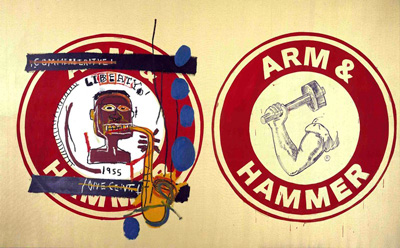

Ever the genius at aligning himself with what was most vibrant in contemporary culture, this was also the moment at which Warhol was deep into his collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat, with them creating some of their most icon joint works such as ‘Arm and Hammer’(1984). In some of Warhol’s digital paint-box collages from his early encounter with the Amiga, it is possible to trace not the just the mark of Warhol’s ongoing practice, but also the influences of Basquiat’s ‘twanged’ graffiti like lines and mark making.

Jean-Michel Basquiat And Andy Warhol, Arm And Hammer 1984 © The Estate Of Jean-Michel Basquiat

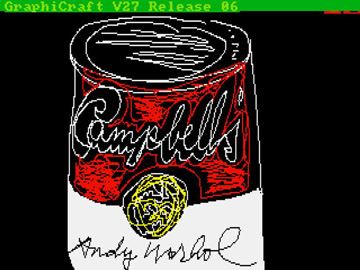

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s, 1985, ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., courtesy of The Andy Warhol Museum

Although Warhol continued to experiment with the Amiga until his death in 1987 (he apparently owned several machines), much of his work was ‘lost’ in what has emerged as an ongoing pressing issue for early digital artists. Often dependant on technologies that become rapidly archaic in the fast-evolving technological domain of computer hardware and software, digital artworks often require complex acts of digital archaeology and restoration to be re-encountered in the present.

Famously, Warhol’s computer artwork remained inaccessible, locked on a series of decaying archaic floppy disks stored in the archives of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. It would take the initiative of pioneering digital artist Cory Arcangel, in collaboration with museum archivists and software engineer Keith Bare from Carnegie Mellon University Computer Club, to excavate and recover these artworks in 2014.

| Voice of America (VOA) News.‘Long-lost Warhol Digital Images Recovered’.May 19th, 2014 |

||

These acts of excavation of digital and interactive artworks from the 1980s and 90s, in relation to my practice, will be the subject of more in-depth examination elsewhere, both in Dr Anjalie Dalal-Clayton's essay ‘Technological Journeys in the Work of Keith Piper’ and in my examination of the 'Relocating the Remains CD-Rom' entitled 'How the Futurist Archive became Archaic'.

I was unaware of Andy Warhol’s early use of the Commodore Amiga. However, by the late 1980s, I had become aware of the computers image making potential and was drawn to invest in an Amiga 500, the low-cost, cut-down ‘domestic’ version of the original Amiga 1000. Released in 1987, the Amiga 500 significantly shipped with an adaptor allowing one to output its screen to a standard PAL TV and also record it to video. This, along with an additional ability to digitise images from other sources and eventually to animate images through time, saw the Amiga emerge for me as a key production tool across the late 1980s and into the early 1990s.

In the next post I will explore my use of the Amiga during the 1990s as a means of exploring a language of the glitched, trembling image and animated ‘twanged’ line.