Notes on the Research and Development of a multi-channel video project as part of Jet-Black Futures.

From the 6th chapter of the ‘Apocalypse of John of Patmos’, (also known as the Revelation of St John) we encounter the following account. (King James Translation 1611)

i

And I saw when the Lamb opened one of the seals, and I heard, as it were the noise of thunder, one of the four beasts saying, Come and see.

|

ii

And I saw, and behold a white horse: and he that sat on him had a bow; and a crown was given unto him: and he went forth conquering, and to conquer.

iii

And when he had opened the second seal, I heard the second beast say, Come and see.

|

iv

And there went out another horse that was red: and power was given to him that sat thereon to take peace from the earth, and that they should kill one another: and there was given unto him a great sword.

v

And when he had opened the third seal, I heard the third beast say, Come and see.

|

And I beheld, and lo a black horse; and he that sat on him had a pair of balances in his hand.

vi

And I heard a voice in the midst of the four beasts say, A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine.

vii

And when he had opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see.

|

viii

And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.

Over the centuries waves of writers have struggled to impose interpretivist logic to this, and other dense passages from the Apocalyptic writings of John of Patmos. From ‘Historicists’ to ‘Preterists’, these writings have been applied to ‘Eschatological’ speculation discussed elsewhere. |

In Search of Working Drawings. (Graffiti in a Cave)

As with many ancient texts, no original manuscript exists for the Apocalypse of Saint John. Reportedly, some commentators, principally within the Greek Orthodox church, propose that the original was written directly onto the walls of the cave in Patmos, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, said to have been occupied by the hermitical writer.

The notion of this apocalyptic vision first existing as a work of extended graffiti scrawled sequentially onto the walls of a cave by an isolated hermit is a fascinating one. This would certainly explain the labyrinthine and sometimes repetitive structure of the writing. It becomes fascinating to re-imagine it as a diagrammatic scrawl. An extended flow-chart of scribbled allusions. It’s frenetic texts and symbols becoming the obsessive doodling of an esoteric recluse. A work which was as much graphic and visual, as it was textual.

The aesthetics of graffiti, diagrammatic, spontaneous, interspersing fragmented texts with cartoonistic drawing and mark making, is a visual device that has always interested me as a visual artist.

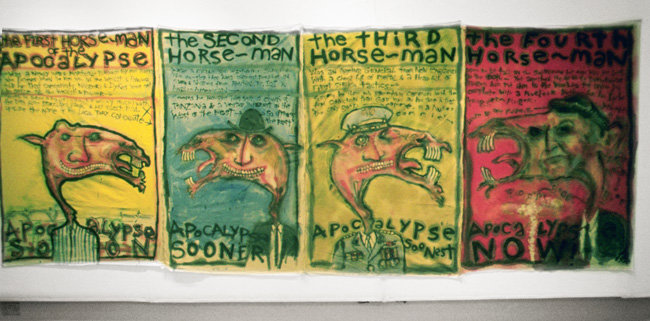

In 1984, I played with the aesthetics of the cartoon in combination with raw hand-written texts with two works that visited the metaphorical narrative of the ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’. The first work, created in early1984 was exhibited at Battersea Arts Centre, London in November-December 1984, in what was to be the final show by the Blk Art Group. This was a large-scale work painted on four cotton bed sheets stitched together, and using pigment, wax and flour. Its use of extreme caricature and it raw physical quality was heavily influenced by contemporary political cartoonists such as Gerald Scarf and Ralph Steadman.

However, this work proved to be physically unstable (due to the use of wax and flour) and the theme was revisited later in 1984 having moved to the RCA in London. The theme of the Four Horsemen were revisited in the form of four free hanging canvas banners produced initial for the exhibition ‘New Horizons’ held at the G.L.C Royal Festival Hall in January 1985, and re-shown in 1986 at the ICA London as part of New Contemporaries.

This work featured the combining of crudely rendered bodies of four figures taken from the politics of the 1980s, each with a grotesque cartoon-like horse’s head. This juxtaposing of the horse’s head on a human body had been influenced by the sculptural work of Malcolm Poynter who had presented a Lecture on his work in the early 1980s at Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham where I was an undergraduate student.

Malcolm Poynter. Second Horseman of the Apocalypse 1981 Lifesize paper pulp mixed media. |

It is however the use of aggressively hand drawn diagrammatic and cartoon-like imagery in combination with graffiti-like texts that most interests me here. In terms of artists emerging from the mainstream western modernist and post-modernist tradition who have most explored this form, it has unquestionably been Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) whose work engages me most closely.

Emerging initially out of New York Graffiti milieu of the late 1970s as the enigmatic SAMO, Basquiat overlaid the ‘urban’ with an intense intellectual engagement with art world canonical figures such as Cy Twombly, Jean Dubuffet, A.R. Penck and Andy Warhol.

This combination left us, over the span of a brilliant but tragically short career, with a body of work which according to Franklin Sirmans, ‘appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting, and married text and image, abstraction, figuration, and historical information mixed with contemporary critique’ (p91). Rachel Smith builds on this, citing Basquiat as ‘record(ing) a new epic, in the style of what Derek Walcott calls the “New Adam” constructed from the tension created by the assimilation of the visual traditions of both the colonizer and the colonized. He combines Medieval European artistic tropes with those emanating from Africa and the Caribbean’.

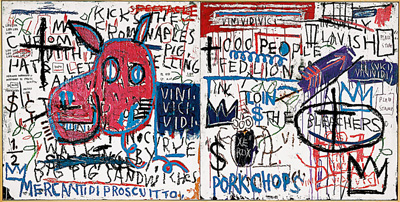

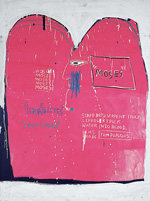

From within Basquiat’s extensive oeuvre, I am currently drawn to two works from 1982, a key developmental phase in his evolution as an artist. Both works are currently in the collection of the Guggenheim Bilbao, and aesthetically represent two opposing poles in his approach to text and mark-making from the early 1980s. ‘Man from Naples’ is a densely composed criss-cross of overlapping texts and signs surrounding an elementally rendered, painterly donkeys head. These signs, symbols and texts proliferate to colonise the whole surface of a twin panel diptych.

Jean-Michel Basquiat. Moses and the Egyptians (1982) Acrylic and oil stick on canvas. 185.9 x 137 x 4 cm. Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa |

|

This graphic/painterly language owes much to the complex graffiti of SAMO, and provides tantalising clues around how symbolic signs, texts and storytelling can be organised and sustained across the extended vertical plane of the canvas, the urban wall, or for that matter, the wall of a cave in Patmos occupied by an obsessive hermit.

For me, as a video maker and screen based interactive artist, these devices also open up a secondary set of storytelling possibilities. These can be explored through the possibilities of animating these symbols, signs and texts through time, to make what Rachel Smith describes as ‘twanged lines’, tremble (to borrow a term from Chris Marker via the Otolith Group).

In the next post ‘The Twanged Line Trembles’, I will use the late work of Basquiat as the entry point to a discussion around my creative interest in the 'animated' line, the 'scribble', the 'glitch' and the 'blur'.

Keith Piper April 2020

I have just become aware of this wonderful animated video made for Ted-Ed by art historian Jordana Moore Saggese, and art director, Héloïse Dorsan Rachet. ‘The chaotic brilliance of artist Jean-Michel Basquiat’ (2019), not only presents an excellent summary of Basquiats life and work, but also reflects many of the aesthetic concerns that inform this body of research.

The chaotic brilliance of artist Jean-Michel Basquiat - Jordana Moore Saggese.Lesson by Jordana Moore Saggese, directed by Héloïse Dorsan Rachet. Ted-Ed. Feb 2019